Вступление

Танго – “социальный” танец с длинной историей профессиональной деятельности на “периферии”. От “живой” музыки до “ДиДжеев”, от преподавания танцев до “просто потанцевать” – кругом есть практика и история платных услуг. Как и у других “социальных” танцев, у танго также есть и история соревнований, особенно во время “Золотого Века”. Например, Петролео, прославленный тангеро и “танцор внаем”, начал свою карьеру соревнуясь на чемпионатах милонг. Сегодня, как и тогда, многие дороги в профессиональное танго начинаются на соревнованиях. Справедливо утверждать, что понятие соревнования не чуждо миру танго.

В наши дни вершиной соревнований танго является Чемпионат Мира По Танго (Campeonato Mundial de Baile de Tango), истоки которого в 2003 году. Этот чемпионат помог многим сегодняшним профессиональным танцорам начать карьеры и, таким образом, внес лепту в популяризацию Аргентинского танго вокруг мира. Чемпионат открыт всем – можно записаться в квалификационный раунд и оттуда продвигаться вверх. В отличие от бальных соревнований, в чемпионате танго нет жесткой обязательной программы, так что, теоретически, нет необходимости “зубрить” программу, стремясь удовлетворить жюри. Можно “лишь” учиться танцевать – постичь музыкальность, движение, связь в паре – словом, стать хорошим “социальным” танцором – и надеяться прилично выступить в категории “салон” Мундиала. Такова, по крайней мере, теория. В то же время, отсутствие обязательных элементов, вокруг которых нужно строить занятия, привносит риск: члены жюри, не имея общей, идентичной платформы, могут судить по разному, и выводам жюри может не хватать объективности. А можем ли мы судить об объективности жюри? Могут ли судьи возвыситься над своими предвзятостями и корнями? Как, вообще, велика разница между победителями и вторым местом? Другими словами, что, вообще, может нам сказать о танго соревнование? В этом эссе мы, вооружившись каплей статистики, глянем на Чемпионат Мира 2016 (салон), данные для которого, как теперь принято, общедоступны (напр., финал).

Забегая вперед, скажу, что мы найдем на удивление полные ответы на все эти и другие вопросы, например:

- Можно отличить плохих танцоров от хороших, и хороших от отличных

- Чем лучше танцоры, тем труднее различить их уровень со стороны пользуясь ныне существующей системой оценок. В финале порядок мест практически случаен.

- Судьи привносят в оценки свои предвзятости, которые могут сильно отражаться на оценках, как случайным образом, так и систематично. Например, судьи много выше оценивают якобы более сильных танцоров, даже если это одни и те же танцоры!

- Судьи часто и сильно разнятся во мнениях, и могут постоянно друг другу противоречить!

Я надеюсь, что моя попытка привнести данные в журналистику танго окажется многим познавательной и интересной. Я старался сделать материал доступным к пониманию людям, не подкованным в статистике, и при этом вызывающим доверие специалистов. Весь код прилагается.

Итак, вперед!

Чемпионат мира: участники

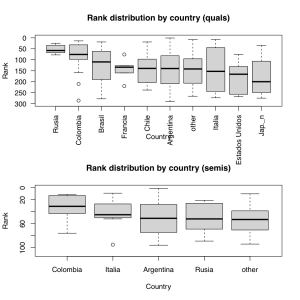

Чтобы поразмяться, начнем со стран, представленных в Чемпионате. Не считая прямых квалификаций в полуфинал и финал, участники представляли 27 стран. Во многих случаях, эти страны были представлены лишь горсткой участников, но некоторые страны прислали большие и порой очень сильные делегации. Такая широкая репрезентация вне Аргентины позволяет нам задать наш первый вопрос: а есть ли страны, в которых культура танго особенно сильна? Например, часто доводится слышать о сильном профессиональном танго в Колумбии и России. Итак, График 1 – распределение мест по странам. Действительно, Россия и Колумбия, со средними местами ~60 и~80 из 400 пар, соответственно, выделяются среди других стран! Более того, эти результаты достигают статистической значимости – крайне маловероятно, что это случайное отклонение от среднего! (Здесь и далее, мы опускаем детали. Зануды вроде автора могут пройтись по коду сами.) Итак, похоже, есть две страны с необычно сильными профессионалами (ф основном профессионалы, все-таки, тренируются, покупают билет, и едут соревноваться в БА).

Figure 1 Results by country in the qualifiers and semifinals. Note strong qualifying round performance from Russia and Columbia.

А как же Аргентина? – спросит скептик. График 1 подразумевает, что именно Аргентина вполне посредственна! Но всем известно, что Аргентинцы очень хорошо выступают в Чемпинатах Мира, и обычно выигрывают. В чем же дело? В том, что Аргентина, как организатор и хозяин первенства, приводит самую большую а, главное, и местную, делегацию – 289 пар в квалификационном раунде (из 404). То есть, Аргентина средняя потому, что она в большинстве, и она дома. Более дальние и сравнительно не самые богатые страны, вроде Колумбии и России, не могут прислать всего лишь “неплохих” танцоров – таким танцорам накладно ехать в БА без шансов на успех. Поэтому из более бедных или более дальних стран в Аргентину попадают в основном профи. Этот феномен, как мне видится, и отвечает за относительный успех этих стран.

Полуфиналисты отсеиваются в квалификационном раунде, попадают с чемпионатов своих стран, или занимают высокие места в Campeonato de baile de ciudad (городском чемпионате БА). В полуфинале, учитывая много более высокий уровень танцев после отсева, Россия более не выделяется, а Колумбия выделяется лишь едва-едва. Огромное количество аргентинцев сказывается – в полуфинале 71 пар из 108 – из Аргентины.

Чемпионат Мира: человеку свойственно ошибаться

Часть I: Танцоры

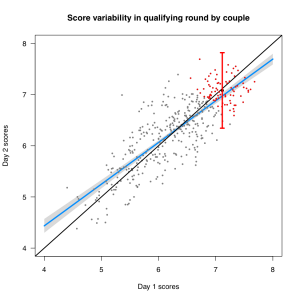

Мы начнем расследование темы грешности человека с Графика 2.

График 2. Результаты квалификационного дня 2 против дня 1 для одних и тех же пар. Пары, прошедшие в полуфинал, показаны красным. Черная линия показывает идеальное и ожидаемое равенство, где все пары выступают одинаково хорошо оба дня, а синяя линия показывает настоящее взаимоотношение между результатами двух дней. 67% величины результатов дня 2 объяснимы днем 1. Красная вертикальная линия показывает разброс результатов средней пары меж дней (95% разброса). То есть, все, кого в пределах погрешности наблюдений, можно было назвать потенциально лучшими, прошли в полуфинал (это хорошо). С другой стороны, все пары, прошедшие в полуфинал, примерно равны в глазах судей если смотреть на результаты двух дней (это плохо).

Каждая точка графика соответствует одной паре. На оси иксов результаты первого дня, а на оси игриков – второго. Красные точки соответствуют парам, прошедшим в полуфинал через квалификационный раунд. Черная линия показывает идеальную ситуацию: судьи присуждают парам одинаковые результаты в каждый из дней. Синяя линия показывает настояшее взаимоотношение между результатами, присужденными каждой паре в каждый из дней. Красная вертикальная линия показывает разброс результатов средней пары за два дня. То есть, в 95% процентах случаев, жюри даст каждой паре оценку, колеблющуюся в пределах одного полного очка. Красная линия центрирована на средней по результатам паре из прошедших в следующий раунд. Обратите внимание, что разброс оценок, центрированный на средней квалифицировавшейся паре, примерно равен разбросу результатов всех пар, прошедших в полуфинал. Что это означает? Оптимистично, можно утверждать, что процесс сработал, и пары, прошедшие в полуфинал, прошли бы опять, если бы соревнования повторились. На этом хорошие новости более или менее заканчиваются, и на более пессимистичной ноте можно сказать, что пары, прошедшие в полуфинал, были примерно равны в глазах судей – что судьи, похоже, не смогли бы повторно оценить выступления в том же порядке. В другие дни пары продолжали бы быть довольно близки друг к другу по сравнению с разбросом оценок каждой пары, с колебаниями в местах из-за небольшой разницы в уровне каждой пары ото дня в день и из-за флуктуации оценок и состава жюри. Если это смелое утверждение справедливо, то средние результаты пар, прошедших в полуфинал, мало что могут сказать нам о местах в самом полуфинале: мы ожидаем сильные помехи среди этих заведомо сильных пар ввиду случайных флуктуаций. Ранги выступающих, стало быть, должны, в таком случае, быть нестабильны. Вот это-то, как раз, легко проверить! Насколько существенно взаимоотношение между результатами пар, прошедших в полуфинал, между полуфиналом и квалификационным раундом?

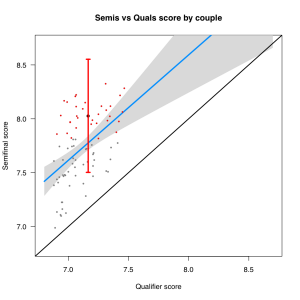

График 3 Результаты полуфинала для пар, прошедших из квалификационного раунда. Пары, прошедшие в финал, выделены красным, а красная вертикальная линия показывает разброс в оценке средних финалистов, и центрована как раз на средней паре.

График 3 однозначно доказывает: здесь все неоднозначно. Зависимость есть, но она невелика. Результаты квалификационного раунда объясняют всего 24% оценок в полуфинале! Другими словами, если пары, прошедшие в полуфинал из предыдушего раунда, раньше явно выделялись из большинства, то теперь, как и в прошлом раунде, пары, прошедшие в следующий раунд (финал), примерно равны и, что хуже, не очень отличаются, в пределах разброса, от пар, в финал не прошедших. Две трети пар могут претендовать на примерное равенство в пределах разброса! Обратите внимание, что не все полуфиналисты представлены в этом графике: мы исключаем те пары, которые попали в полуфинал из других турниров. Итак, скудные хорошие новости из этого раунда: другое жюри, оценивающее те же пары, оценило их в порядке, отдаленно напоминающем предыдущий. Плохие новости: порядок в основном другой. Что хуже, этот график выглядит немного странно, особенно по сравнению с предыдущим: все результаты в полуфинале, для всех пар, выше, чем в квалификационном раунде – все точки выше черной линии. С этим мы разберемся чуть позже, а пока возьмите этот факт себе на заметку.

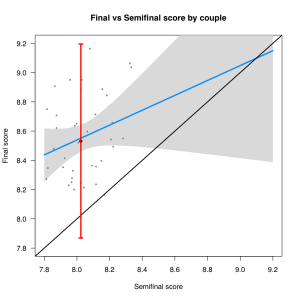

Дабы закончить наше расследование стабильности оценок, глянем на график 4, показывающий пары, прошедшие из полуфинала в финал.

График 4. Результаты финала и полуфинала для одних и тех же пар. И снова результаты выше, чем в предыдушем раунде!

Теперь результаты совершенно иные. С точки зрения статистической значимости, соотношение между оценками пар в финале и полуфинале “наводит на мысль” о каком-то взаимоотношении, но не более того. Глядя на график, можно предположить, что и вовсе нету никакого соотношения. Но пары-то, заметим, одни и те же!!! Статистика, впрочем, говорит, что, возможно оно и есть, но небольшого количества финалистов с предысторией в полуфинале недостаточно для уверенности. И опять все пары сильнее, чем раньше. Постараемся это запомнить, а пока резюмируем выводы из графиков 2-4.

- В квалификационном раунде, где пары соревновались дважды, разброс оценок был примерно 1.5 очка. В более поздних раундах, игнорируя систематическое улучшение оценок, разброс по сравнению с предыдушими раундами был примерно таким же как и между двумя днями квалификационного раунда

- Победители квалификационного раунда все как раз и поместилисъ в разброс 1.5 очка от средней пары, прошедшей в полуфинал

- В каждом последующем раунде, результаты прошедших пар все менее похожи на предыдущие раунды

- В каждом раунде, результаты всех прошедших пар неуклонно растут

Объяснение, которое наиболее правдоподобно и которое обобщает первые три наблюдения, таково: совокупность правил оценки и формата соревнований, а также и разница в составе жюри, не дают возможности оценить выступление точнее, чем +/- 0.7 очка. Могут ли сами танцоры быть настолько непостоянны? Маловероятно. В первую очередь мы можем так полагать потому, что с каждым раундом турнир должен отбирать все более сильные и, вероятно, постоянные пары. В первом раунде это очевидно происходит. Однако разброс оценки с каждым раундом почти не падает! Если бы разброс оценок зависел в основном от танцоров, то он бы падал с каждым раундом, а не оставался бы тем же или рос. Итак, мы подозреваем судейскую систему.

Часть II: Судьи

На данный момент мы установили, что судьям свойственно совершать небольшие, но заметные и случайные, ошибки в оценках – ошибки, которые с каждым раундом, похоже, все более влияют на порядок мест, от “немного” в квалификационном раунде до “решающе” в финале. К сожалению, такие случайные ошибки не являются единственными ошибками в судействе. Вероятно, наиболее серъезно отсутсвие объективности в оценочном процессе. Я не утверждаю определенно, что судьи предпочитают пары по внешнему виду, возрасту, или другому параметру – я не могу этого доказать на основе имеющихся данных. Однако, я определенно утверждаю, что предрассудки судей играют большую роль. Вернемся к наблюдению 4 выше. С каждым раундом, результаты каждой пары, не вышедшей из игры, растут. Этот факт иллюстрирован в Графике 5.

График 5. Этот график показывает результаты всех пар, прошедших в финал, которые начали соревнования в квалификационном раунде. Ось игриков показывает разницу в оценке каждой пары по сравнению с их оценкой в квалификационном раунде. В самом квалификационном раунде наблюдается знакомый нам разброс результатов по сравнению со средней парой.

Итак, все пары неуклонно и заметно улучшаются с каждым раундом. Невозможно предположить правдоподобность такого феномена! Более вероятно, что судьи считают пары в более высоких раундах более сильными, чем пары в более ранних раундах, даже если это одни и те же пары!!! Такая склонность подтверждать свое мнение в статистике называется confirmation bias. Склонность отражать раунд в оценке навряд ли сильно отражается на порядке мест. Однако, какие еще предвзятости таятся в оценках?

Установив предвзятость в одной из форм, взглянем на некоторые другие аспекты оценок жюри. Оказывается, можно примерно оценить, на что смотрят судьи, группируя результаты по некоторым “направлениям” оценок жюри. Для этого, привлечем подход под названием “метод главных компонент”. Мы не будем вдаваться в детали, но лишь заметим, что главные “компоненты”, вероятно, описывают самые важные аспекты оценок. По крайней мере, они группируют танцоров по отношению к главным аспектам консенсуса судей. Графики 6-8 показывают главные направления вариации в полуфинале и финале (полуфинал представлен дважды: все танцоры, и только те, кто прошел в финал). Стрелки представляют мнения индивидуальных судей и порядок мест танцоров (сортированный по консенсусу мнений). Стрелки обозначены именами судей.

График 6. Результаты полуфинала. Большинство судей соглашаются о результатач, и хушая треть, середина, и лучшая треть танцоров в обшем отделимы в первой “компоненте” оценок. Эта компонента объясняет 39% оценок, что немного, но и немало.

График 7. Результаты полуфинала лишь среди пар, прошедших в финал . Согласие судей намного менее заметно – оно объясняет 21.5% оценок. Двое судей полностью несогласны в главных двуx “компонентах”!

График 8 Судьи продолжают не вполне соглашаться в оценках. Главная компонента объясняет 35.5% разброса оценок. Мнения судей все еще склонны диаметрально расходиться.

Главный смысл этич графиков таков: рассматривая только главное направление вариации, вероятно, описывающее технику или музыкальность танцоров, консенсус жюри не очень единогласен. При этом, больше всего разногласий в финале.

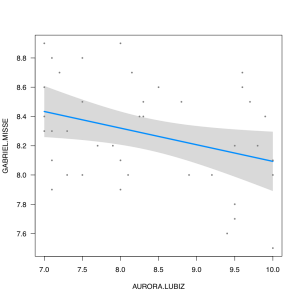

Метод главных компонент немного абстрактен, так что приведем более понятный пример. Заметим, что Аврора Любиз и Габриел Миссе часто несогласны друг с другом по методу главных компонент. Посмотрим же, в Графике 9, насколько расходятся оценки, данные ими танцующим парам.

График 9. Судьи порой расходятся во мнениях. Оценки Габриеля Миссе слабо противоположны оценкам Авроры Любиз. Стоит заметить, что его оценки также намного ближе друг к другу, нежели оценки Авроры. Габриел, фактически, считает, что финалисты малоразличимы в уровне танго – мнение, поддерживаемое нашими моделями. Аврора же силъно разделяет танцоров по уровню, с ясными победителями и проигравшими.

Может ли быть, что невозможно сравнивать танцоров выше определенного уровня? Для сравнения, посмотрим на наших кузенов, танцоров бального танго, участников соревнования Блэкпул, одного из самых престижных бальных соревнований в мире.

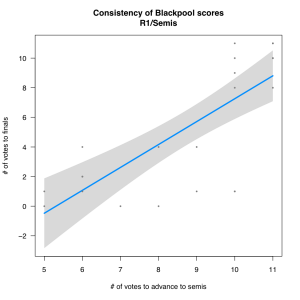

График 10. Постоянство оценок в Блэкпул. Количество голосов судей, рекоммендующих пару в следующий раунд, очень коррелируется между первым раундом и полуфиналом (глядя на одну и ту же пару). Несмотря на много меньшее число участников, статистическая значимость этого взаимоотношения сравнима с соотношением результатов квалификационного раунда и полуфинала (см. выше). Следует полагать, что оценки выступлений в Блэкпул более аккуратны и единогласны среди судей.

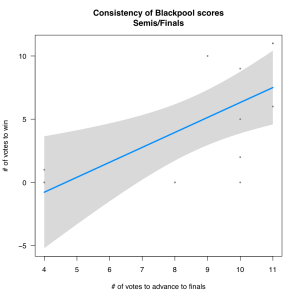

График 11. Даже среди финалистов, оценки в Блэкпуле более повторимы между раундами, несмотря на меньшее количество участников, чем в чемпионате мира по Аргентинскому танго.

Графики 10 и 11 демонстрируют довольно высокую стабильность оценок пар между раундами, примерно как стабильность оценок между квалификационным раундом и полуфиналом Аргентинского танго выше. Тогда мы называли тот уровень неважным, оставлявшим существенное равенство между парами, переходящими в следующий раунд. Однако можно подметить, что соотношения в Блэкпуле нелинейны (формы бумеранга) и недооцениваются нашим подходом. Проблема в том, что в Блэкпуле, похоже, не использовали оценки, а вместо этого “вызывали” танцоров в следующий раунд. По крайней мере, именно такие данные мне удалось найти. Следовательно, требуется другой способ оценки соотстветствия результатов раундов. Не вдаваясь в детали, оценки много более стабильны, чем они выглядят и более напоминают способность оценить победителей квалификационного раунда в Чемпионате Мира. Почему оценки в Блэкпуле более стабильны? Возможно, что это, отчасти, результат присутствия обязательных элементов и, соотстветственно, более высокая стандартизация оценок качества танца.

Прощать божественно

Значит ли все вышеизложенное, что система соревнований безнадежно сломана, и оценивать танго среди профессионалов невозможно? Вовсе нет. Профессионалов вполне возможно оценить от любителей – фактически, именно это и происходит в квалификационном раунде. Наверняка существуюшую систему можно улучшить. Например, судьям можно устраивать “тренировочный раунд”, где они оценивали бы одни и те же пары на видео с тем, чтобы оценить разногласия жюри и прийти к консенсусу до начала соревнований.

Стоит ли оценивать танго, как бальные танцы, по системе обязательных элементов? Наверное, нет. Гармония и красота танго – в его импровизационных корнях. Разнообразие для танго – кислород, и не стоит им поступаться ради улучшения системы оценок. В конце концов, победители будут нас учить лишь тому, в чем сами сильны. А пока признаем, что судьи – люди, что они стараются судить хорошо и, наверное, будут пытаться улучшить систему, если эта и подобная информация к ним попадет.

В дополнение ко всему сказанному выше, запомним, что профессиональные танцоры и преподаватели склонны к непроизвольной предвзятости и не могут оценить одних и тех же танцоров одинаково в разных раундах. Следовательно, как танцоры, не будем это забывать, выбирая партнера или партнершу для танды, и стараться не учитывать исподволь возраст, красоту, или другие поверхностные факторы. Не стоит также забывать, думая об оценках танцоров в Буэнос Айресе, что лучший танцор в комнате, пожалуй, не намного лучше второго лучшего, если их оценивать в соревновании. Пусть эти данные будут зеркалом для каждого.

Я надеюсь, что вы нашли эту статью полезной и интересной. До встреч на милонгах!

Boris

Код добавить не удалось из-за настроек безопасности. Пишите если хотите посмотреть.